This post is by NCTE member R. Joseph Rodríguez.

Something that gets banned can get an adolescent’s attention.

And from my experience as a teacher, this is proven true across two centuries. (I began teaching in 1992.)

And from my experience as a teacher, this is proven true across two centuries. (I began teaching in 1992.)

“I’ve started reading banned books. That’s my new reading list, Mr. Rodríguez,” declares Aquilino, a senior student in my language arts class.

His thoughts and imagination get my full attention.

“Which one did you start with, Aquilino?” I ask.

“Lord of the Flies. Well, I started with Lord of the Flies, but they’re so many more books I might just read two at a time. Is that a good idea though, Mister?”

“If that keeps you reading, I say go for it. Keep going in your reading,” I respond.

Kimberly, a junior, jumped right into reading The Color Purple and The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story during our structured independent reading time.

“I think they’re both part of a connected story,” she notes.

Books, even the banned and challenged ones, open minds.

I am coming to this decision and declaration about books—more and more each day—as I teach language arts and reading.

In my thirty-year career as a teacher and researcher, book defenders and I fight and win battles to get books in the hands of students and their families. Overall, we support more digital books for students’ devices and personal libraries, so they can read and dive inward to know and trust themselves.

In my thirty-year career as a teacher and researcher, book defenders and I fight and win battles to get books in the hands of students and their families. Overall, we support more digital books for students’ devices and personal libraries, so they can read and dive inward to know and trust themselves.

Only through reading words can young people name the worlds they inhabit. Evidently, students become consciously awakened and culturally aware as the Brazilian scholar Paulo Freire reminded people around the world years ago (74-75, 87-88).

The struggle to get banned and challenged books on digital and nondigital shelves demands immense courage and strength, especially to keep going in this literacy pursuit for democracy. Many more teachers, librarians, and parents can attest the bans of books by LGBTQ authors and authors of color faced each week in schools and libraries across the country.

My push for access to banned and challenged books is mostly at the local level, beginning with my own classroom library, school library, and Little Free Library, but also extends to town, city, and county libraries.

Our literacy work is not for the faint of heart, but for those seeking to do the advocacy work that harnesses more youth minds and worlds through words and books.

Some of my book advocacy translates to getting school bookrooms opened to students, books on classroom shelves, and book spaces in our hallways, so students can have book choices to consider for their reading enjoyment.

Some book advocates attend school board and public meetings to say the following to the elected and appointed: These books exist for young readers. Read them first and involve the public’s input before making decisions. Let the process begin now and with all of us.

Book reading must not be reduced to banishment, excerpts, formulas, or measurement as advanced by BookLooks.org. Besides, most books that are banned or challenged are unread by the select few or by groups that ban them in the first place without firsthand knowledge of the content and author’s body of work.

Moreover, books cannot be used as punishment or for extrinsic motivation. Frankly, why not just read for the pleasure of it, rather than solely for bubbling in a multiple-choice test form, answering comprehension questions as a robot, getting a grading score for an authority figure, or measuring student populations against one another? Books are more than a standardized test.

Piggy, one of the characters in Lord of Flies by William Golding, says in the opening chapter, “I expect there’s a lot more of us scattered about. You haven’t seen any others, have you?” (2). I believe he speaks of the adventuresome, the imaginative, and the survivors.

Piggy’s words can apply to book advocates and defenders: more of us exist. And we must keep rising up.

The goal of providing book access is led by teachers, librarians, and supporters. We do this work with locked arms and in collaboration, cooperation, and unison as we put the US Constitution into action. We must promote the freedom to read, learn, and understand.

Each week my students tell me of more books—many banned and challenged by non-readers or fearmongers. The students reveal the numerous book titles that illuminate their lives though. Their stories they find in fiction, nonfiction, graphic art, and poetic forms, which reveal the dilemmas and scenarios they face while growing up in this century.

In our everyday, we face immense realities: global pandemics, political upheavals, nature’s wraths, and beginning and changing relationships through the tempests of censorship squads. When the misinformed ban or challenge books, what they’re essentially saying is that they refuse to read a book in its entirety and fear learning and understanding.

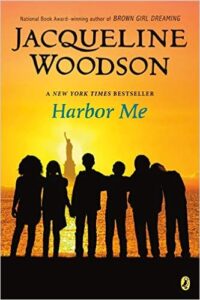

However, authors such as Elizabeth Acevedo, Jason Reynolds, Erika L. Sánchez, Jacqueline Woodson, and many others write books for young people and that can challenge the censors and dividers among us. The members of the American Library Association, Freadom USA, and National Council of Teachers of English gather in response as influencers for our students’ right to read and learn.

In the introduction to the 2016 edition of Lord of the Flies, Stephen King explains:

A successful novel should erase the boundary between writer and reader, so they can unite. When that happens, the novel becomes a part of life—the main course, not the dessert. A successful novel should interrupt the reader’s life, make him or her miss appointments, skip meals, forget to walk the dog. In the best novels, the writer’s imagination becomes the reader’s reality. It glows, incandescent and furious. (xix)

The classics and contemporary classics that continue to be banned and challenged, from the past to the current century, glow in the lives of our students. Equally important, our students are just as incandescent and furious as the authors who write and publish; they must unite across pages, chapters, and books across the country.

In the novel Harbor Me by Jacqueline Woodson, my students and I read, “Ms. Laverne said every day we should ask ourselves, ‘If the worst thing in the world happened, would I help protect someone else? Would I let myself be a harbor for someone who needs it?’ Then she said, ‘I want each of you to say to the other: I will harbor you'” (34).

In the novel Harbor Me by Jacqueline Woodson, my students and I read, “Ms. Laverne said every day we should ask ourselves, ‘If the worst thing in the world happened, would I help protect someone else? Would I let myself be a harbor for someone who needs it?’ Then she said, ‘I want each of you to say to the other: I will harbor you'” (34).

Our worlds can be enlarged when we read one or two books at a time similar to my students Aquilino and Kimberly. We must harbor them as young people and readers.

May our imaginations flourish, and may books, even those banned and challenged, fuel our students’ minds and hearts—and our very own—for the common good.

Note: The names Aquilino and Kimberly are pseudonyms to protect the students’ identities.

A previous version of this essay first appeared in Fredericksburg Standard–Radio Post, October 5, 2022, page D3.

R. Joseph Rodríguez teaches language arts and reading and prepares future teachers at St. Edward’s University. He is the coeditor of English Journal and author of several books including This Is Our Summon Now: Poems (FlowerSong Press, 2022). Joseph lives in Fredericksburg, Texas. Catch him on Twitter or Instagram at @escribescribe.

Works Cited

BookLooks.org. http://booklooks.org. Accessed 13 Oct. 2022.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 30th anniversary edition. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos, Continuum, 2000.

Golding, William. Lord of the Flies. 1955. Penguin Books, 2016.

Hannah-Jones, Nikole, et al. The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story. One World, 2021.

King, Stephen. Introduction. Lord of the Flies, by William Golding, 1955, Penguin Books, 2016, pp. xvii-xix.

Walker, Alice. The Color Purple. Penguin Books, 1982.

Woodson, Jacqueline. Harbor Me. Nancy Paulsen Books, 2018.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.