This post is reprinted with permission from Moving Writers.

When students are asked to introduce themselves in writing, it can be difficult figuring out the best way to stage this encounter between self and stranger, writer and audience. For my seniors who are drafting college application essays, the first attempt is often characterized by tentatively offered assertions about their motives for applying, or the unintentional listing of their activities in narrative form. This year, I found that sharing mentor texts for writing between first and second drafts was the sweet spot: this gave them a chance to get an exploratory sketch on the page, to find out what wording felt clunky and which parts “sung” before I chatted with them one on one.

This time, though, I didn’t just reach for my “usual suspects”: essays written by former students. It’s always helpful seeing how other college applicants tackled the task in previous years, but I didn’t want my current students to imagine there was one formula for introducing themselves or that you had to stick with one genre of writing to look for dynamic craft moves. Instead, I shared with them a set of mentor texts that modeled moves offering idea provocation or structure provocation: new possibilities for sharing ideas about one’s own coming of age story, as well as for the sentence structure that would serve as the best vehicle for conveying these ideas.

Explode the Cliché

When writing about issues or hobbies they care about, it can be challenging for students to express their love in a manner that feels fresh. It’s difficult trying to express passion for something without straying into the well-trod, hackneyed territory of clichéd love expressions. My suggestion to students: rather than avoid talking about “falling in love,” run straight toward the cliché and make it their own. Combining the expression of “being in love”–with all its connotations of romance–with an unexpected object can make the reader sit up and take notice.

Aimee Nezhukumatathil does a wonderful job of modeling this move in her essay, “Corpse Flower,” found in her book of illustrated nature essays, World of Wonders. I’ve written previously about how I use World of Wonders as a mentor text: it can be mined endlessly for inspiration. In this essay, Nezhukumatathil shares her love for the corpse flower, an atypical object of affection. What my students and I came to notice, however, is how deftly she introduces herself via the plant and how this self-introduction hinges on affection for a love object known for its foul odor–the stench of the plant unequivocally earns it one of its nicknames, “the Amazing Stinko.” Towards the end, she expands her ruminations on the corpse flower into a awe-filled digression about newly discovered facts about plants:

While conferencing with students, I put the question to them: How could you present your love for something in an unexpected way? As we study the sentence from Nezhukumatathil’s essay, we observe how her use of parallel structure expands and intensifies the image of being in love. Appreciation for the corpse flower extends to other plants that, unbeknownst to most humans, communicate and help each other. To underscore the usefulness of expanding an image through parallel structure, I write an example of my “being in love” for my students:

Acknowledge the In-Between

Prior to giving students time to rework their drafts, I build in time for class journaling. Small, generative writing exercises can provide a foothold for revision ideas simmering in nascent form. After reading Stuart Kestenbuam’s marvelous poem, “Joy,” we zoomed in on the imagery related to the life cycle of the Monarch butterfly:

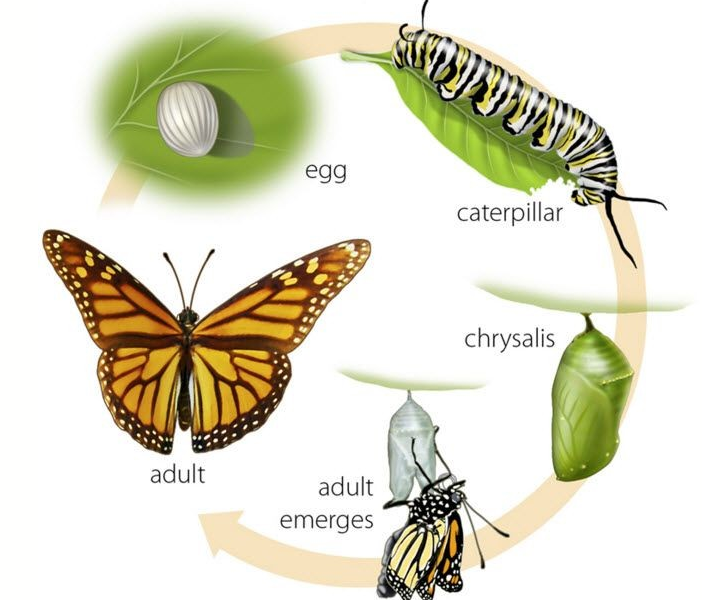

During writing conferences, a few students mentioned that they were having trouble structuring their essays. They had an idea about some aspect of their identity they wished to share, but felt stuck in the attempted articulation. To help them flesh out their ideas, I asked them to study the following illustration. Using the metaphor of the Monarch butterfly’s life cycle, where would they place themselves in the stages of development?

When asked to share, the responses were unexpected. Instead of identifying with one stage of development, many students placed themselves “in between” stages:

- “I’m not quite an adult, not quite a child…maybe I’m in chrysalis.”

- “I actually feel like I’m in a holding pattern, unsure of where to land.”

- “I feel like I’m on the cusp, caught in between.”

I encouraged my students to see the inability to map themselves neatly onto the life cycle as a positive. Bringing this tension into their narrative of self could enhance the storytelling stakes. Perhaps they could introduce their interest in a potential field of study from the lens of their child self, curiously surveying the world from a small height. Maybe toggling back and forth between their younger and contemporary impressions of a role model would best communicate their journey into gratitude for this helpful presence in their life.

Acknowledging the ways one’s identity is a work-in-progress can add texture and dimension to a self-introduction. Kestenbaum’s poem acknowledges that every part of the butterfly’s story involves transformation. While we may look at the illustration and see four distinct stages of metamorphosis, major changes to the life form, as suggested by the black, orange, and white wing patterns visible in the pupa covering, are occurring throughout.

Honor the Seed Planting

During a conference, a student shared her frustration: “It seems like a lot of college essay prompts want me to share a light bulb moment. And I haven’t had one ‘a-ha!’ moment or epiphany about what I want to do with my life. So I’m not sure what to write.” This student knew what she wanted to study in college, but the ability to plot this decision-making into a narrative seemed elusive.

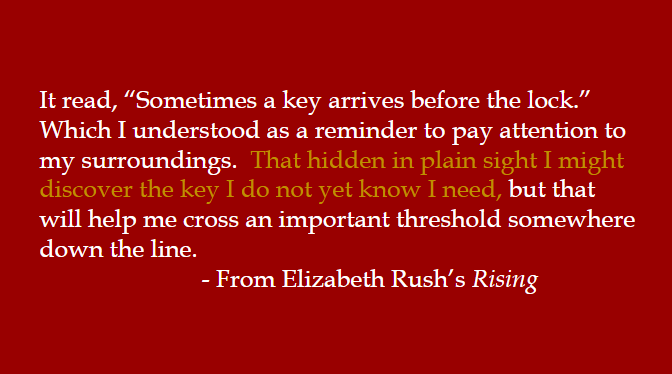

I responded sympathetically. Of course, it would be easier if we could communicate our journey into maturation in a neatly plotted line from point A to point B. But a narrative that could hit more subtle notes could be just as interesting, if not more so. Her dilemma reminded me of a key metaphor used in Elizabeth Rush’s book, Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore. A brilliant, sobering work of reportage, Rush’s book illuminates the devastating effects of our rising seas on both human and nonhuman coastal communities. Prior to moving back to New England and visiting the tidal marshes in Rhode Island, she taped a quotation from an essay on Alzheimer’s to her computer monitor:

While visiting coastal communities, Rush learns the name tupelo, a word referring to a tree that once helped marsh waders know what topography to expect. When we say the word now, she says we refer to trees whose roots couldn’t handle saline inundation. The particular ecology it relies on to be rooted–that precious balance between salt water and fresh water–is gone. The image of the key, arriving before we know how to use it, ensues as an important image. What warnings will we heed in time and which names will continue to signify the living will depend on how we pay attention and how we act on what we observe.

Despite the urgency of her message, Rush introduces the key image undramatically and returns to it more than once. It gathers resonance as we register what is disappearing. I encouraged my student to think about how she could subtly introduce an image that suggested a pattern detectable in her own behavior, a pattern that gestured towards her growing interest in the field of psychology. After thinking about it, she experimented with writing about puzzle pieces: how she frequently thought about human behavior in terms of puzzle pieces that fit together or as pieces that don’t quite fit. In the dynamic process of coming of age, of becoming the person we wish to be, indicating a pattern in our own behavior might be more suggestive of who we are than expressing one moment of epiphany.

Xochitl Bentley teaches 11th and 12th grade ELA at Cleveland High School in Reseda, California. She is a Teacher Leader with the Cal State Northridge Writing Project. In 2017, she was chosen to participate in the Japan-U.S. Teacher Exchange Program for Education for Sustainable Development. She is passionate about active environmental stewardship and environmental justice. You can connect with her via Twitter @dispatches_b222 or via email at xochitl.bentley@lausd.net.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.