This post was written by NCTE member Mary Lee Hahn. It’s part of Build Your Stack,® an NCTE initiative focused exclusively on helping teachers build their book knowledge and their classroom libraries. Build Your Stack® provides a forum for contributors to share books from their classroom experience; inclusion in a blog post does not imply endorsement or promotion of specific books by NCTE.

In the past few months, white America has taken a couple of baby steps in learning American history. More whites now know about the Tulsa Massacre of 1921 and Juneteenth than ever before. As a white teacher, I believe it’s my responsibility to continue my own learning, and I hope we can all do this and make plans to bring what we learn into our curriculum. Picture book biographies are a great place to start. Say their names. Lift them up. Make American history whole.

My classroom library continues to evolve as I learn and grow. In the summer of 2020, I gathered this stack. This is not a definitive resource. This stack is a reminder to start with the books that are on your shelf or in your school library. This stack is a reminder that books can be used not just to center Black excellence. They are also the books you can go to for mini lessons on the power of endpapers, using the format of poetry in writing a nonfiction text, comparing and contrasting across a theme or topic, creating a dual timeline, using flashback, or studying the ways illustrations and text work together.

Along with teaching a more complete and honest version of American history, these books are a reminder to be intentional about all the ways we can center Black excellence in our classrooms.

Begin with Frederick Douglass, who lived an amazing life that spanned a significant era of the history of our nation: he was born into slavery, was involved in resistance and abolition, championed women’s rights, experienced emancipation, and lived to see the 13th Amendment ratified. Douglass’s story makes it clear that Black history is American history.

Begin with Frederick Douglass, who lived an amazing life that spanned a significant era of the history of our nation: he was born into slavery, was involved in resistance and abolition, championed women’s rights, experienced emancipation, and lived to see the 13th Amendment ratified. Douglass’s story makes it clear that Black history is American history.

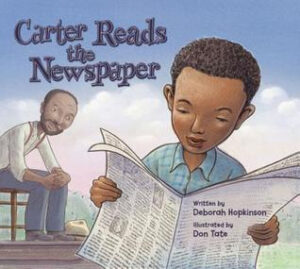

The endpapers of Carter Reads the Newspaper could be the starting point for a year-long study of history, beginning with kings, queens, and pharaohs in Africa, and continuing on to the activists and politicians of today. Let’s continue the work of Carter G. Woodson, who spent his life championing Black history by establishing Negro History Week in 1926. This week eventually became Black History Month. Let’s weave Black history into all of American history.

The endpapers of Carter Reads the Newspaper could be the starting point for a year-long study of history, beginning with kings, queens, and pharaohs in Africa, and continuing on to the activists and politicians of today. Let’s continue the work of Carter G. Woodson, who spent his life championing Black history by establishing Negro History Week in 1926. This week eventually became Black History Month. Let’s weave Black history into all of American history.

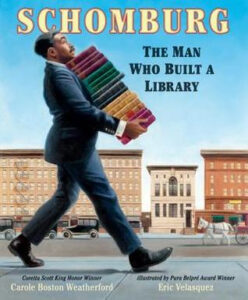

Whereas Carter G. Woodson was supposedly told by a Harvard professor that Black people had no history, it was Arturo Schomburg’s fifth-grade teacher who told him that, and who sparked his quest to collect the books and documents that proved her wrong. This collection became the Schomburg library in Harlem. Close readings of each of the poems in Schomburg: The Man Who Built a Library can lead to a deeper understanding of both Schomburg and luminaries of Black history.

Whereas Carter G. Woodson was supposedly told by a Harvard professor that Black people had no history, it was Arturo Schomburg’s fifth-grade teacher who told him that, and who sparked his quest to collect the books and documents that proved her wrong. This collection became the Schomburg library in Harlem. Close readings of each of the poems in Schomburg: The Man Who Built a Library can lead to a deeper understanding of both Schomburg and luminaries of Black history.

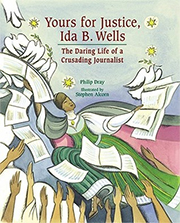

Like the lives of Douglass, Woodson, and Schomburg, Ida B. Wells’s life was defined by the power of reading, writing, and speaking. She should be known not only as a journalist, but as a journalist who fought against Jim Crow laws and lynching and for desegregation and women’s suffrage. The blend of realism and symbolism in Stephen Alcorn’s illustrations in Yours For Justice, Ida B. Wells will deepen the reader’s understanding of Wells’s life and work.

Like the lives of Douglass, Woodson, and Schomburg, Ida B. Wells’s life was defined by the power of reading, writing, and speaking. She should be known not only as a journalist, but as a journalist who fought against Jim Crow laws and lynching and for desegregation and women’s suffrage. The blend of realism and symbolism in Stephen Alcorn’s illustrations in Yours For Justice, Ida B. Wells will deepen the reader’s understanding of Wells’s life and work.

Fannie Lou Hamer’s super power was her singing voice—and her belief in and work for voting rights, civil rights, and women’s rights. A timeline of American history would show that the lives of Douglass, Woodson, Schomburg, Wells and Hamer all overlap, and in some cases, intersect.

Fannie Lou Hamer’s super power was her singing voice—and her belief in and work for voting rights, civil rights, and women’s rights. A timeline of American history would show that the lives of Douglass, Woodson, Schomburg, Wells and Hamer all overlap, and in some cases, intersect.

History can be found in more than just timelines and politics. We need to teach our students that all of us MAKE history with our lived experiences. History is in the lives of our artists and our sports sheroes and heroes.

Not only was Josephine Baker an amazing dancer in the Roaring Twenties, but she worked against racial discrimination, spoke alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington, and lived her truth by adopting twelve children of different races and from different countries.

Not only was Josephine Baker an amazing dancer in the Roaring Twenties, but she worked against racial discrimination, spoke alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington, and lived her truth by adopting twelve children of different races and from different countries.

Tyree Guyton used his art as community activism to lift up and save the Detroit neighborhood of Heidelberg.

Tyree Guyton used his art as community activism to lift up and save the Detroit neighborhood of Heidelberg.

Alice Coachman’s determination and focus on her dream led to her being the first Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal in the 1948 London Summer Olympics.

Alice Coachman’s determination and focus on her dream led to her being the first Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal in the 1948 London Summer Olympics.

Cassius Clay (before he changed his name to Muhammad Ali) also won Olympic gold in 1960. He used his fame to be a positive role model. This book can be used as a mentor text for nonfiction text structures in the way it uses flashback.

Cassius Clay (before he changed his name to Muhammad Ali) also won Olympic gold in 1960. He used his fame to be a positive role model. This book can be used as a mentor text for nonfiction text structures in the way it uses flashback.

Which brings us to today, and the sisters—Venus and Serena Williams (also Olympic gold medalists)—who have changed so much for Black women in sports and the sport of tennis with their power, craft, and sense of fashion.

Which brings us to today, and the sisters—Venus and Serena Williams (also Olympic gold medalists)—who have changed so much for Black women in sports and the sport of tennis with their power, craft, and sense of fashion.

I’ll repeat what I started with—It is the responsibility of teachers to continue learning, and to make plans to bring what we learn into our curriculum. Picture book biographies are a great place to start. Say their names. Lift them up. Make American history whole.

Mary Lee Hahn is a teacher-poet. She has taught fourth or fifth grade for 35+ years and is the author of Reconsidering Read-Aloud. Her poems can be found in more than a half-dozen anthologies. She collects her poetry at Poetrepository.

Mary Lee Hahn is a teacher-poet. She has taught fourth or fifth grade for 35+ years and is the author of Reconsidering Read-Aloud. Her poems can be found in more than a half-dozen anthologies. She collects her poetry at Poetrepository.

NCTE and independent bookstores will receive a small commission from purchases made using the links above.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.