This is an excerpt from Chapter 5, Catching Tigers in Red Weather: Imaginative Writing and Student Choice in High School, by Judith Rowe Michaels (NCTE, 2011).

While it’s important to help students see and hear and wonder at a poem unfolding on the page as they read or listen, it may be even more crucial for them to experience discovery and surprise as a poem of their own takes shape.

For some, the prospect of writing a poem can feel overwhelming—what to write about, how to start, how to decide whether to rhyme, where to break stanzas and lines if they’re not using rhyme or meter, how to “put in” figures of speech. I may show them my “Bear Game” poem at this point so they can see one way of starting—from a notebook entry and a specific object and situation. I may talk about some options I perceived and discarded as I drafted—why I rejected using stanzas, for instance, or trying out a traditional form such as a sonnet. (“Bear Game” has a sonnet-like “turn” about two-thirds of the way through but none of the conventional rhyme schemes or iambic pentameter.)

I might discuss why I used certain words and phrases from the original notebook entry and how I kept reading aloud as I drafted the poem because that not only helped me hear where to break lines and change words for better sounds but also seemed to keep ideas and feelings flowing.

But the kids need to meet a live poet who’s not their daily teacher. So I like to bring in a visiting poet early in the writing process, preferably someone of a different age, gender, or race than mine. This person needn’t be from outside the school, though when we have the money, I do invite an established poet to spend several days working in all the ninth- and tenth-grade classes.

One can find poets through a state arts council, or through writers-in-the-schools programs; I’ve invited poets I meet when I give or take workshops and attend writing conferences. But another teacher, or a student’s parent, or one of our alumni—or even a talented twelfth grader—can be an effective guest artist, depending on the strength and accessibility of their work and their ability to connect with teenagers.

This year we have a new poet in our department, a young woman who’s studied in Oregon with Dorianne Laux and whose sample class, a poetry workshop, impressed me when she came to interview. I invite her to give this workshop to my students. Kate Westhaver talks to the kids about why she writes poetry: that it’s a love–hate relationship because it makes her think but also confuses and scares her.

She says that she reads a lot of poems—in books, magazines, online—and hears them at live readings and slams, but sometimes these poems baffle her. “And I think that’s okay,” she says. “I can still enjoy a poem even when it confuses me. It’s okay to not understand, not ‘get’ every line. Sometimes I just enjoy the sounds, or maybe certain lines speak to me.”

For her, writing a poem has an element of play.

“If I let go of making sense, I can enjoy making sound. The music of the poem can inspire random beauty and surprising connections for me. Things I didn’t know I knew. Lines that make me wonder, ‘gee, how did I come up with this?’”

Kate hands out copies of e. e. cummings’s “anyone lived in a pretty how town.” I’m happy that we have another “story poem” here—another life “journey,” though a somewhat different one from “Charlie Howard’s Descent”—and one that offers both mystery and music.

Definitely, as Kate said about her own writing, it contains lines that will make us wonder, “How did he come up with that?” She asks us to listen with pencils in hand as we take turns reading the stanzas aloud. “Mark lines that you like and moments you find surprising, including rhymes, capitalization, and punctuation.”

When the reading ends, students have discovered some new options for their own poems: varying refrains, off-rhymes mixed with true rhymes, four-beat lines, the absence of punctuation and capitalization, and a whole new take on language—or, to use a word most of them don’t know—syntax.

The poem shakes up a lot of their assumptions about writing, let alone writing poetry. But they seem to agree with Kate that one can enjoy a poem even—or especially?—when it confuses them. And they love the refrains: the varied order of the four seasons and of the “sun moon stars rain.”

Kids pick out other favorite lines—“how children are apt to forget to remember” and the whole idea of “no one” being in love with “anyone.” They wonder what a “how town” is, what it means to sow your isn’t or dance your did, and they agree that “up so floating many bells down” may not make sense but it’s got “a feeling.”

Garret’s looking worried. “I like it, but it doesn’t mean anything, does it?”

“I like it because it seems like this sad love poem,” Jen says. “‘No one’ loves ‘anyone’ so much that she ‘laughed his joy and cried his grief,’ and then when he dies she kisses his face. And they’re buried side by side. That’s true love.”

“Yeah, but,” says Peter, “if you put capital letters on them, they’d be characters, but with lowercase, it could be that nobody loves this guy—I mean, like in the second stanza it says women and men ‘cared for anyone not at all.’ So that makes it really sad. Like a love poem with no love in it?”

Kate avoids doing what Billy Collins describes as “tying a poem to a chair and beating it with a rubber hose.”

She invites us to go on thinking about the poem on our own and moves us into her writing exercise. First, she invites us to get up, stretch, and find new seats. Then she has us each divide a sheet of paper into quarters, number them, and listen to four excerpts from four pieces of music that she has on her iPod.

She tells us that listening to music often gets her started writing a poem. “Do any of you do homework to music? What music fosters creativity for you?” she asks them. As we begin to listen, we’re to write whatever comes into our pencil, no censoring, just keep the pencil moving—“whatever words the music brings to you. Don’t worry about writing sentences or making sense. Don’t consciously try to write about the music, to describe it or analyze it. Just let the words come while the music plays. Just let go of making sense. Stay silent even between the excerpts, and shake out your hand if you need to at those breaks.”

I write along with the class, but I also jot reminders to myself of what kinds of music Kate has chosen—just my impressions, though I do want to get titles from her later on:

- “very soft strings, grave, formal music;

- pipe flute breath very Eastern;

- percussive log drum;

- a mix of vocal and instrumental, soprano hum on the ah vowel with jazzy scat style.”

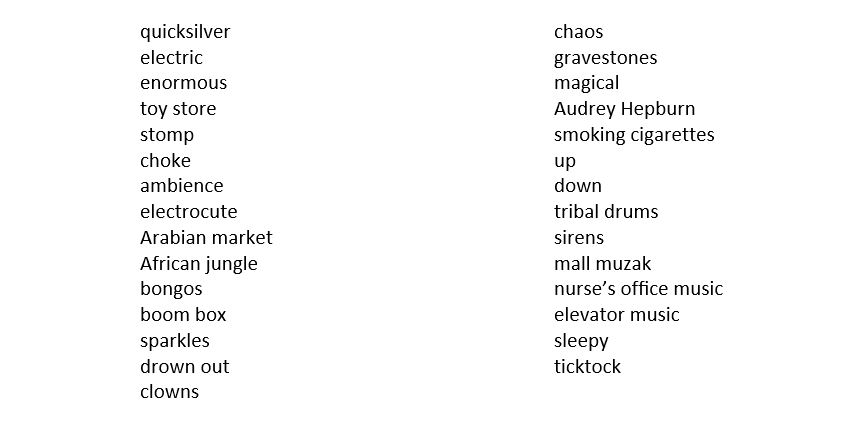

Kate invites students up to the board to record favorite words or word combinations from their writing. The board fills up fast:

Then we get an assignment: “Steal any four words or phrases you like from the board along with material from your own writing and create at least ten lines of poetry. You can change, manipulate, any of this material and also add new things.”

The kids are excited. Some are already starting before Kate has finished giving directions.

We haven’t established any criteria for assessing these poems. I don’t plan to grade them or even write comments at this stage. But the next day volunteers read their pieces aloud, and after applause or finger snapping, I ask readers to say at least one thing they like about their own piece. At times, I expand on these comments: “Yes, Sarah, the way you used that refrain made the feeling of the speaker go deeper, for me, anyway. And it gave the poem a structure—like a song. That’s a technique others of you might want to try.”

As we go around the circle and hear each writer’s comment, I ask for volunteers who can remind us of anything else from that particular poem.

I want the students to realize they don’t need a copy of the poem in front of them to respond to hearing it. The kind and manner of response may be different when we work from memory—more spontaneous, more tentative, more visceral and less analytical. It could be as simple as “Could you read that first part over again? It had some words I really liked the sounds of.”

Gradually, if we listen to enough poems together this way, the students will find they can experience a poem more fully—notice and remember, feel more.

Judith Rowe Michaels is poet in residence and English teacher at Princeton Day School in Princeton, New Jersey, as well as a poet in the schools for the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation. She is a member of the nine-women performance and critique group, Cool Women. Michaels has published three collections of poems, Ghost Notes, Reviewing the Skull, and The Forest of Wild Hands, and has authored two books for NCTE in addition to Catching Tigers in Red Weather: Risking Intensity and Dancing With Words.

Read a sample chapter from Catching Tigers in Red Weather or order a copy from the NCTE Store.