This post was written by NCTE members Wendy J. Glenn and Ricki Ginsberg.

In our recent article in Research in the Teaching of English, we explored the disconnect that high school readers labeled as struggling perceived between their reading identities and experiences in a traditional English course and Young Adult Literature (YAL) elective.

The students’ identities as readers manifested differently across these two classroom contexts. The students of our study deconstructed their experiences in the traditional classroom spaces, built new conceptions of their reading selves in the unique classroom setting of the YAL course, and in the process, assumed greater agency in shaping their individual reader identities. Thus, we advance the argument that differing classroom contexts can provide students with varying levels of opportunity to reject and/or accept ascribed reader identities.

This reminds us of the value of classroom and school contexts, the possibilities that come with inviting students to engage as readers in school rather than engage in school reading, the benefits and risks of reimagined relationships between students and teachers and students and peers, and the possibility that young adult literature in and of itself offers implications for reader agency.

The YAL Course Elective

A Typical Class Session:

- 84 minutes every other school day

- 15 minutes discussing books and sharing recommendations

- 20 minutes learning about new genres, forms, trends, or other book-related topics

- 20 minutes meeting with book groups

- 30 minutes silently reading self-selected texts and/or talking quietly with peers and/or the instructor about their titles

Process:

- No completion deadlines

- Reading progress tracked, and students encouraged to engage with diverse texts from the classroom library

- Teacher/peer conferences for differentiation and evaluation of personal effort

Assessment:

- Student-generated projects

- Personal documentation of reading

- Class participation

- Online participation on a social networking website

What We Found

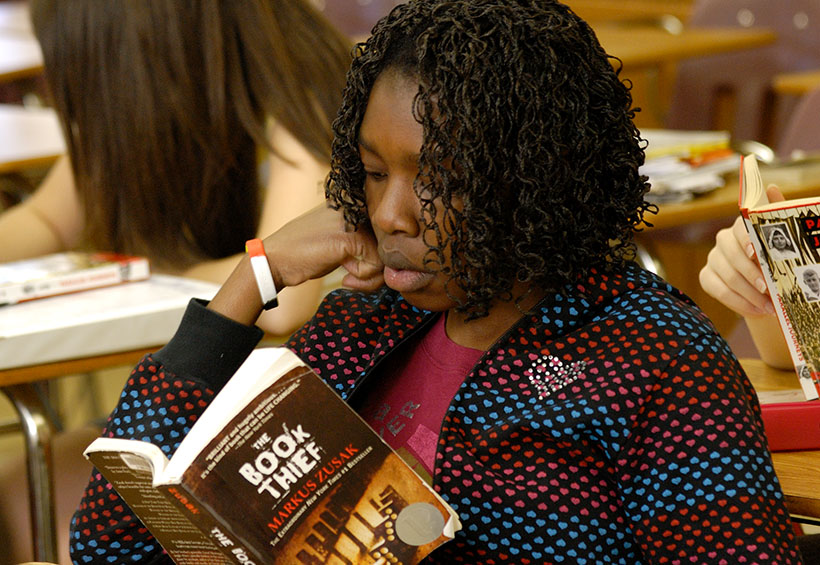

Through their participation in the YAL elective that invited resisting behaviors by honoring individual reading preferences, readers labeled as struggling redefined their identities in meaningful ways.

Traditional English Courses: A Game, with Students as Captive Players

Participants positioned teachers in the traditional English classroom as rule makers and referees and students as captive players. They said that the singular form of control they possessed in this game was centered on whether to participate. Those who exerted control by choosing not to play sometimes did so with fervor and defiance.

As Aaron explained, “The required school reading? I didn’t read any of that. Ever. I just didn’t read it. . . . I mean, they gave us the list of stuff, and there could have been good titles in there, but I just never gave it a second glance. I was just like, “’I don’t want to do this.’ I just threw it out.”

Although this resistance might be admirable in the way it reflects students’ commitment to their beliefs, participants reported the dangers of nonparticipation as impactful on their academic success in the English classroom. And yet, they chose not to engage anyway.

YAL Course: Students as Agents and Architects

In contrast, participants described how the YAL elective provided space for the exploration and development of more liberating reading identities. Students in the YAL class equated the freedom to choose with increased motivation and engagement in reading.

In describing why choice mattered to him, Devon explained, “It’s more motivating to read. You’re not as restricted, so there’s more freedom and independence. . . . It’s like, your freedom to read.”

Nia noted how the different approach influenced her success as a reader: “[In YAL], you basically get to read at your own pace. So it’s not, ‘Oh, you have to read chapter seven by tomorrow.’ I’m a really slow reader, and I have a lot of issues with reading, so when I have a specific time, it puts more pressure on me and makes it a lot more difficult for me to read. But when I just have whenever, when there’s no specific time, I tend to read better and faster and more efficient.”

The YAL course experience also invited students to participate in a community of readers for the first time. Julia stated, “Yeah, I actually didn’t know that a lot of people like to actually read . . . and learn about other books, too, like me.”

Participants also described a vision of the YAL teacher as respectful partner rather than rule maker. Nia explained, “She used to have me try different books, but she would never push me. . . . She would just be like, ‘Here. Try this book. If you don’t like it, bring it back and we will find you another one.’ I guess it is just respecting the kid’s opinion, really, is what it comes down to.”

Participants advanced, too, the idea that they, as readers, had the right to read titles that exist outside the boundaries of those sanctioned in school, a recognition that grew directly from the YAL course experience. And in the YAL course, students reported reading much more. Participants shared that they rarely did any of the assigned reading in their English classes that year—or ever.

Four students laughed when asked whether they read more or less in the YAL class. Devon said, “I never read for English. I only skim. And for Young Adult Literature, I actually read the books.”

Demetrius added, “[In YAL,] I read a lot more. … I don’t think I’ve read one [book] yet in English. I think I’ve read six books so far [in YAL].”

This engagement manifested itself in students’ enthusiasm for reading as captured by Nia’s assertion, “When you go to Young Adult Lit, it’s like ‘Yes. Finally, this class is here. I get to read.’”

Related Resources of Potential Interest

Buehler, Jennifer. Teaching Reading with YA Literature: Complex Texts, Complex Lives. National Council of Teachers of English, 2016.

Ginsberg, Ricki, & Wendy Glenn (Eds.). Critical Approaches for Critical Educators: Engaging Critically with Multicultural Young Adult Literature in the Secondary Classroom. Forthcoming.

Hayn, Judith, Jeffrey S. Kaplan, & Karina R. Clemmons (Eds). Teaching Young Adult Literature Today: Insights, Considerations, and Perspectives for the Classroom Teacher. Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Kittle, Penny. Book Love: Developing Depth, Stamina, and Passion in Adolescent Readers. Heinemann, 2012.

Lesesne, Teri. Reading Ladders: Leading Students from Where They Are to Where We’d Like Them to Be. Heinemann, 2010.

Miller, Donalyn. Reading in the Wild: The Book Whisperer’s Keys to Cultivating Lifelong Reading Habits. Jossey-Bass, 2013.

Wendy J. Glenn is Professor of Literacy Studies, Co-chair of Teacher Education, and Chair of Secondary Humanities in the School of Education at the University of Colorado Boulder. She teaches courses in the theories and methods of teaching literature, writing, and language, and her research centers on literature and literacies for young adults, particularly in the areas of socio-cultural analyses and critical pedagogies.

Wendy J. Glenn is Professor of Literacy Studies, Co-chair of Teacher Education, and Chair of Secondary Humanities in the School of Education at the University of Colorado Boulder. She teaches courses in the theories and methods of teaching literature, writing, and language, and her research centers on literature and literacies for young adults, particularly in the areas of socio-cultural analyses and critical pedagogies.

Ricki Ginsberg is Assistant Professor of English Education at Colorado State University. She teaches courses in reading and writing pedagogies, teaching and research methods, and young adult literature, and her research interests include educational equity, teacher education, multicultural young adult literature, critical pedagogies, and the recruitment of teachers of color.

Ricki Ginsberg is Assistant Professor of English Education at Colorado State University. She teaches courses in reading and writing pedagogies, teaching and research methods, and young adult literature, and her research interests include educational equity, teacher education, multicultural young adult literature, critical pedagogies, and the recruitment of teachers of color.