This is an excerpt from the article “Remembering Freedom Songs: Repurposing an Activist Genre” in the September 2018 issue of College English.

***

This post was written by NCTE member Elizabeth Ellis Miller.

After we were attacked, we’d come back to the church, and somehow always we’d come back bleeding, singing “I love everybody” . . . the more we sing it, the more we grow in our ability to love people who mistreat us so bad.—Dorothy Cotton, Sing for Freedom (115, 117)

No more long prayers, no more Freedom songs, no more dreams—let’s go for power.—Stokely Carmichael, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle (8)

Together, Dorothy Cotton and Stokely Carmichael chart the rise and fall of an activist genre. In the first epigraph, Cotton reflects on the significance of freedom songs during the classic phase of the Civil Rights Movement that occurred between 1954 and 1965.

She highlights the ways that freedom songs, a key activist genre, offered activists a way to respond and to resist while also demonstrating a commitment to peace and interracial unity. Cotton’s words, thus, name the defining social action of freedom songs in the Civil Rights Movement: nonviolence leveraged through spiritual love.

By taking up freedom songs in response to White violence and oppression, activists deployed songs such as “Ain’t Nobody Gonna Turn Me ‘Round” to enact the goals and strategies of the Black freedom movement through peaceful social action.

However, as Carmichael’s words in the second epigraph indicate, the genre of the freedom song, important as it was for a time, did not persist as the key social action for activists throughout the Civil Rights Movement.

As the 1960s wore on and the goals and strategies associated with nonviolence came to be questioned by large groups of activists, the need for the freedom song genre dissipated. As many looked to exchange spiritual nonviolence for Black Power, freedom songs became less valuable as strategies of activism and for organizing large groups.

In response to this cultural deprecation, the present study investigates this unique moment in freedom songs’ history as an activist genre. Where previous examinations of freedom songs have sought to understand their rise to rhetorical power for activists, this essay explores a different, corollary question.

What happened to the genre of freedom songs as it diminished in usefulness and leaders began to question the songs? Considering this question, I study how the genre’s value to users dissipates because of changes in context and exigency, and I name this phenomenon rhetorical depreciation.

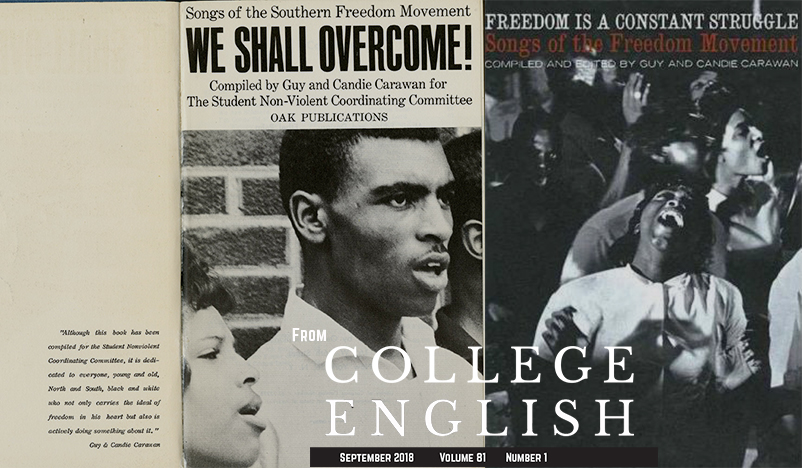

To unpack freedom songs’ rhetorical depreciation and investigate how genre users respond to it, I examine the work of activists Guy and Candie Carawan, a husband and wife duo. The Carawans observed freedom songs’ dissipating rhetorical efficacy and subsequently turned to framing freedom songs in a new way: instead of prompting activists to sing in protest, they encouraged remembering instead.

Sensing rhetorical depreciation, I argue, they responded and crafted memorial texts that centered on freedom songs, working to reveal that the songs could now be useful as sites for remembering civil rights events, successes, and key figures.

This essay focuses on one such memorial project, the Carawans’ Freedom Is a Constant Struggle. This text, a 1968 songbook, recasts freedom songs as sites of memory. Examining Freedom Is a Constant Struggle, we see how, rather than abandoning and forgetting freedom songs because they were falling out of practice as protest, users like the Carawans worked to repurpose this genre for a new exigency—remembering the songs and their work in the immediate past Civil Rights Movement. With this collection, they attempted to change freedom songs’ observable social actions from nonviolent protest to memories of the movement. To support these shifts to the songs, they leveraged an available memorial genre, the songbook.

In examining freedom songs as sites of genre change, I join such scholars as Dylan Dryer and Risa Applegarth in investigating the question of how genres transform and are adapted and especially the role that genre users play in creating changes.

Elizabeth Ellis Miller is an assistant professor of English at Mississippi State University. Her research addresses genre theory, rhetorics of social change, and rhetorical history and has also appeared in Rhetoric Review. She is working on a book about religious genres and mass meetings during the Civil Rights Era.

Read the full article “Remembering Freedom Songs: Repurposing an Activist Genre.”

Interested in reading more from College English? Subscribe!