This post was written by NCTE member Yolanda Whitted.

The March for Our Lives—It washed over me like a tsunami, every bit of hurt and pain I should have felt, but never allowed myself to, because I had to be strong. I couldn’t get caught up in my feelings because I had to teach my students how to use their voices, and I couldn’t do that if I turned into a soft, blubbering idiot—or so I thought. . . .

I was only 11 years old the first time I witnessed a murder. I knew the man who was shot, and I saw his face opening as the assailant “unloaded” on him—a term we used to describe what happens when a person shoots someone until there are no bullets left in their gun. His head hanging back on the headrest, neck bent in an unnatural backward curvature, his face opened like a flower blooming, broken and grotesque. I couldn’t look away.

This is the way they eliminated life in my city, Chicago. It wouldn’t be the last time I saw the light go out of someone’s eyes. Over the years, I would lose so many family members, loved ones, close friends, neighbors, and classmates that I stopped counting. It wasn’t the last time I would ask the question, with a quivering chill over my body and a deadening stillness over my mind, “Am I next?”

It wasn’t the last time I would see the repercussions of systematic oppression in my neighborhood, and, when I left Chicago for good, I found I hadn’t escaped that vision of violence and death, because it is so heavily ingrained in every poor urban neighborhood in America. It was the life I chose when I decided to support people like me. My fight and passion brought me to environments that triggered me, and this was simply the cost of being an advocate—I had to be okay with that.

Once I became a teacher and advocate for urban students of color in poverty, my “heart moments” only grew.

On average, over the 15 years I’ve taught and worked with children, I’ve lost about three students each year to gun violence.

Some years I would lose as many as five of the students I fought for, the students I fought with. Some died in domestic disputes, some died because they were simply at the wrong place at the wrong time, while others died because they succumbed to a cycle of poverty they didn’t know how to get away from. They joined their brothers and cousins, their uncles and aunties, their sisters and mothers “in an early grave.”

So, at the March for Our Lives, I stood there trying not to cry, holding back the tears during speech after speech—whispering names in my mind and talking to them, “I’m standing here for you.”

Afraid to speak, I proudly raised my fist in solidarity with speakers as others cheered. I didn’t want to cry because I thought it would never stop if I started. Then, they said her name, “Taiyania Thompson,” and I came completely undone.

I taught her for a brief period at the beginning of the 2017–18 school year when I first moved to Washington, DC. Taiyania, 16, was beautiful, vibrant, focused, and hilarious. Each day, she would come to class, complete her work, and watch The Daily Show with Trevor Noah in my classroom during lunch.

We laughed and hugged each day—we were close—and I used to pick on her about the amount of lip gloss she used, to which she would say, “Don’t hate, Ms. Whitted, you know my lips be poppin’!”

I was teaching at a new school in southwest DC when I received a text message from a former colleague stating that Taiyania had been shot in the head, allegedly by a boyfriend, and was not expected to survive. I broke down as if I had lost my daughter.

At the march, Naomi Wadler, the 11-year-old student at George Mason Elementary School in Alexandria, Virginia, who led her school’s walk-out on March 14, mentioned Taiyania and said, “I am here to acknowledge the African American girls whose stories don’t make the front page of every national paper. . . . These stories don’t lead on the evening news. I represent the African American women who are victims of gun violence, who are simply statistics instead of vibrant girls full of potential.”

That acknowledgment broke my well-maintained façade and an unstoppable deluge of tears flowed for her and every child I lost over the years, for every family member, for every friend, for every community, for every parent, for every pain we’ve all felt.

It was at that moment I realized how hurt I was, how broken I’ve become, how long I had avoided remembering what I had seen, how I never took the proper time to grieve because I always felt beginning to grieve would mean I’d never stop crying. There are simply too many people to mourn.

I realized how much I avoided getting lost in grief by thinking Why should I cry? I’m still alive! They don’t need my tears; they need my action! Now, more than ever, I realize that my voice, my actions, and my successes are theirs.

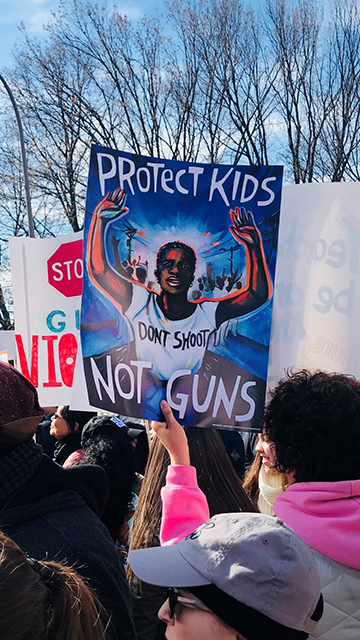

Although attending the march was important to me as a teacher, I was there to make sure I stood in the gap for the many children of color whose lives have been forever altered due to the gun violence that plagues our communities.

Although attending the march was important to me as a teacher, I was there to make sure I stood in the gap for the many children of color whose lives have been forever altered due to the gun violence that plagues our communities.

I was glad people came together to support the students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas in Parkland, Florida; however, the biggest positive about the march and rally for me was that those students created a platform for children of color to speak about and against the violence that has been plaguing their communities for decades.

Edna Chavez, from South Los Angeles, remembered her brother; Christopher Underwood, from Brooklyn, spoke about the loss of his brother; his best friend, Zion Kelly, a DC native, spoke about the death of his twin brother Zaire; Mya Middleton, Alex King, D’Angelo McDade, and Trevon Bosley, all from Chicago, talked about the systematic economic oppression and relentless gun violence plaguing their Chicago neighborhood, and unleashed their personal stories of tragedy, and Martin Luther King Jr’s granddaughter, nine-year-old, Yolanda Renee King, led us in a chant as she expressed her desire to see a gun-free America.

The fact that Parkland students checked their privilege—and gave space for the voices of children who have long experienced anxiety on their way home from school, who have wrestled with the fear that they will lose another family member, friend, or loved one to gun violence—solidified the fact that this movement is one of solidarity and love.

As Parkland shooting survivor Jaclyn Corin so eloquently stated, “We recognize that Parkland received more attention because of its affluence, but we share this stage today and forever with those communities who have always stared down the barrel of a gun.”

By their acceptance and perseverance, our youth are changing the polarity of the political landscape in our country. This gives me great hope.

Because of our young people’s drive, I believe the March for Our Lives is only the beginning of us finally coming together and championing the cause of protecting our children and communities.

Yolanda Whitted teaches middle school English Language Arts and Reading Intervention/Extension at Washington Global Public Charter School in Washington, DC. Read her NCTE Village post “Beautiful Moments.” @PhenomTeacher